What Is Portfolio Allocation and Why Does It Matter?

Portfolio allocation defines how you distribute your investments across asset classes based on your goals, risk tolerance, and time horizon. Diversification, which is sometimes confused with allocation, is a separate principle that involves spreading investments within and across asset classes to reduce risk. While allocation sets the framework for your portfolio, diversification helps manage specific risks inside that framework.

Your portfolio allocation should not remain static. As your circumstances change (financially or personally), your investment mix may also need to change. What seemed appropriate a few years ago might no longer match your current priorities or tolerance for risk.

In most cases, the structure of your portfolio (strategic assets allocation) influences long-term results more than the choice of individual assets. A well-defined allocation keeps your investments aligned with your goals, even during periods of uncertainty or market stress.

Key Asset Classes and Their Traits

Before selecting a portfolio structure, you need to understand the tools involved. Asset classes differ — they serve different purposes, behave differently, and carry different levels of risk. Knowing how each asset typically fits into a portfolio will help you make smarter decisions when building your own allocation. Some drive growth, others reduce volatility, and a few offer flexibility or protection.

Equities (Shares)

Ownership in companies. Can bring long-term growth, sometimes dividends.

- Risk: High. Prices can rise or fall quickly. Affected by market cycles, business performance, and external news.

- Liquidity: High. Most shares can be sold instantly through stock exchanges. Prices are public and updated constantly.

- Horizon: Long-term. Best suited for goals five years away or more. Short-term use is risky due to volatility.

- Returns: High potential returns, especially over longer periods. Often outperforms other asset classes, but with higher volatility.

Fixed Income (Bonds)

Loans to private companies or government entities. Long-term financial instruments with income in the form of interest.

- Risk: Exposure depends on issuer and duration. Interest rate changes and credit events can affect bond prices, especially for long-term or lower-rated bonds.

- Liquidity: Moderate. Bonds can often be sold early. However, the price is often lower than expected in this scenario. Depends on market demand.

- Horizon: Flexible. Some use short-term bonds. Others lock funds for ten years or more. Choice depends on the goal.

- Returns: Moderate. Government bonds offer stable but lower yields. Corporate bonds offer higher returns with added risk.

Index Funds

Funds that follow the performance of a specific market index. Example: Euro Stoxx 50, MSCI Europe. You don’t pick individual shares — you buy the whole group.

- Risk: Moderate to high. Tied closely to market trends — sharp downturns can cause noticeable short-term losses. No active management to reduce drawdowns.

- Liquidity: High. Most are traded daily. You can enter or exit easily.

- Horizon: Long-term. Works best when held for several years. Not ideal for short-term use.

- Returns: Moderate to high. Reflects average market growth over time, with lower fees boosting long-term gains.

Mutual Funds

Pooled investments managed by professionals. They choose assets for the group — shares, bonds, or both. You buy units in the fund.

- Risk: Varies by fund composition. Actively managed, but still exposed to market swings, management decisions, and fees that may impact performance.

- Liquidity: Moderate. Can usually be sold within a few days. Not as quick as cash.

- Horizon: Varies. Some are built for growth, others for income. Read the fund’s strategy before investing.

- Returns: Vary by strategy. Equity-based funds can offer high returns with more risk. Bond-based funds deliver steadier but lower yields.

Cash and Cash Equivalents

Money held or parked. Often used to reduce overall risk. Examples: savings accounts, treasury bills, money market funds.

- Risk: Very low. Returns are small. Inflation may slowly erode value. No market exposure.

- Liquidity: Very high. Cash is available immediately. Most equivalents can be withdrawn within 24–72 hours.

- Horizon: Short-term. Used for capital that may be needed soon. Common for emergency funds or parking money between investments.

- Returns: Very low. Designed to preserve capital, not generate growth. Often fails to beat inflation over time.

Alternatives (Property, Commodities, Others)

Assets outside traditional categories. Examples: real estate, gold, peer-to-peer lending, private equity, cryptocurrencies.

- Risk: Varies. Some are stable, others are highly speculative. Alternative investments are often less transparent.

- Liquidity: Low. Selling may take weeks or months. Prices are not always clear.

- Horizon: Medium to long. Often locked in or difficult to exit early. Suitable for those willing to wait.

- Returns: Varies widely. Some offer high long-term returns (e.g., private equity), others act as stores of value (e.g., gold). Usually comes with liquidity constraints and elevated risk.

Some alternative assets may not be available to retail investors or may require higher capital, legal checks, or regulatory approvals.

Assessing Your Risk Tolerance, Investment Goals and Timeframe

Before deciding how to divide your investments, take a step back. Think about your personal situation. What are you investing for? A home in the future? Regular income? Retirement savings? Each goal has its needs. Your investment allocation should reflect how close or far those needs are. If your target is far off, you may have more room to take risks. If it’s close, protecting your capital becomes more important.

Next is risk tolerance. Risk tolerance is the level of uncertainty or potential loss you’re willing to accept in exchange for possible gains. It is not a certain number. It’s about how you react when the market drops. Do you stay calm and wait? Or do you panic and sell?

There are three main risk profiles:

- Conservative. Focused on protecting capital. Accepts lower returns in exchange for more stability.

- Balanced. Accepts some ups and downs. Aims for moderate growth without taking extreme risks.

- Aggressive. Seeks high returns. Willing to accept losses along the way.

There’s no risk profile suitable for all investors. Each type has its place. The important thing is to choose an approach that matches how you think and what you’re comfortable with. That’s how you move closer to your optimal asset allocation.

Looking at the timing is also helpful. If your investment goal is far in the future, you may have more flexibility to handle risk. If it’s closer, you might prefer something steadier. Your current financial situation matters, too. If you need the money soon, assets with low risk and high liquidity may be more suitable. If your essential needs are already covered, you might be open to taking on more risk for higher potential returns.

In the end, your ideal investment portfolio should reflect your personal circumstances, not some recommendation or someone else’s plan.

Common Asset Allocation Models

Once you understand your goals and risk profile, the next step is to build a structure around them. Asset allocation models help with that. Remember — they are not rules. These asset allocation model portfolios can be a useful foundation for your plan. The aim is to find a balance between return, stability, and access to funds. Each model has trade-offs.

Below are three of the best asset allocation models used by investors worldwide.

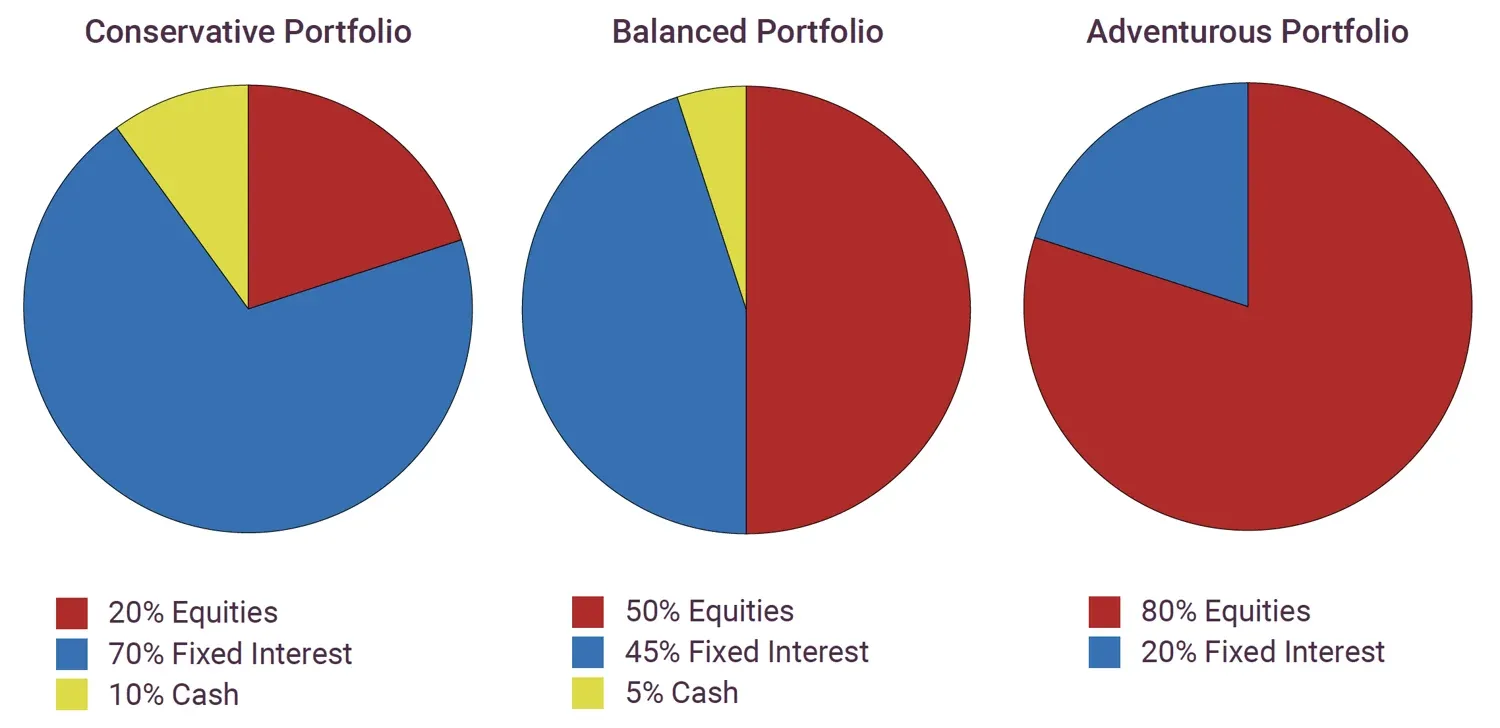

Conservative Allocation

Designed to reduce exposure to market volatility. Prioritises capital preservation and steady income over growth.

Typical split:

- 20-30% equities

- 60-70% bonds

- 5-10% cash or equivalents

This model suits investors who prefer lower risk. It may be useful when funds are needed soon, or when avoiding loss is more important than gaining value. Returns are usually modest. But drawdowns tend to be smaller, too.

Liquidity is moderate to high, depending on the type of bonds and cash instruments included. Stock exposure is kept limited to reduce short-term fluctuations.

For example, a person planning to buy a home in five years or someone entering retirement could choose a conservative split to preserve capital and limit risk during short timeframes.

Balanced Allocation

Aims to find a middle ground. Seeks reasonable growth, but avoids taking excessive risk.

Typical split:

- 50-60% equities

- 30-40% bonds

- Up to 10% cash

This structure fits many medium-risk profiles. It works for investors who want their portfolios to grow over time but also want some protection during downturns.

Compared to the conservative asset allocation portfolio, this one allows more exposure to the market, which increases long-term return potential and introduces more volatility. Still, the bond portion helps smooth out movements during unstable periods.

For example, someone in their 40s saving for their children’s education over the next 10-15 years might prefer a balanced model. It offers growth potential with less volatility, protecting their savings as the goal approaches.

Aggressive Allocation

Focused on long-term growth. Accepts greater swings in value for higher potential gains.

Typical split:

- 70-90% equities

- 10-25% bonds

- 0-5% cash

This model is built for investors who are comfortable with short-term losses. It may suit those who are investing for goals far in the future and can afford to wait through downturns.

Returns on aggressive portfolio allocation can be higher over time, but the path may be uneven. The lower share of bonds provides little insulation during market corrections, so this structure requires confidence and patience.

For example, a 30-year-old investing for retirement in 30+ years could choose an aggressive allocation (e.g., 80% equities, 15% bonds, 5% cash). They have time to recover from market downturns and benefit from long-term growth.

Other Portfolio Allocation Strategies

Standard models, namely, conservative, balanced, and aggressive, cover most needs. However, some portfolio asset allocation models go beyond the basics, offering more flexibility or tailored focus. These strategies are not universal, but each has a clear purpose. They can be especially useful for those looking for simplicity, passive portfolio management, or specific income goals, depending on their financial stage and personal preference.

- Age-Based Portfolio Allocation Model. The rule is simple: subtract your age from 100 (or 110) to get your ideal stock percentage. Pros: easy to apply; adjusts risk over time. Cons: too simplified; doesn’t account for personal goals or risk preferences.

- Target-Date Strategy. You choose a year (e.g., retirement in 2045), and the portfolio adjusts gradually — more conservative as the date approaches. Pros: hands-off; follows a built-in glide path. Cons: may be too slow or too fast for your actual needs.

- Three-Fund Portfolio. One fund for domestic stocks, one for international stocks, one for bonds. Clean and efficient. Pros: broad diversification; low cost. Cons: no flexibility for more complex strategies or preferences.

- Core and Satellite. The core holds stable assets (e.g., index funds). Satellites add tactical exposure — sectors, themes, alternatives. Pros: balance between stability and opportunity. Cons: requires more knowledge and attention.

- Income-Focused Allocation. Aims to generate regular cash flow from bonds, dividend shares, and real investment trusts. Pros: steady income stream. Cons: may lack growth; exposed to interest rate risk.

Notes on Application

Allocation models are not rigid. They offer a starting point — a structure you can adjust as your goals, market conditions, or personal situation evolve.

Even the proportions aren’t fixed. A 60/40 balanced split can shift slightly over time. What matters is staying close to your risk level and keeping your portfolio in line with how you think and what you need.

Also, depending on your country, taxes on income or capital gains may also affect your allocation choices, especially in long-term planning.

Conclusion

Choosing the right asset classes is not about chasing returns — it’s about building a structure that works for you. Start with your goals. Define how much risk you’re comfortable with. Then choose a model that fits both. Use the examples in this guide as a starting point. Pick one that matches your profile, adjust the proportions if needed, and review it once a year. There’s no single best asset allocation — just the one that fits your current situation.

You don't have to start with a perfect plan. But it's important to invest and use money wisely instead of hoarding. A simple setup that reflects your needs today is already a big step forward. Review it regularly, adjust if life changes, and let it grow with you.

Frequently Asked Questions

What asset classes provide less risk?

Asset classes that generally provide less risk include:

- Bonds

- Cash and cash equivalents

- Certificates of deposit (CDs)

- Real estate Investment Trusts (REITs)

How to choose the right asset classes for your needs?

Choosing the right asset classes for your needs involves understanding your investment goals, risk tolerance, and time horizon.

What's the difference between index funds and mutual funds?

Index funds and mutual funds are both types of investment vehicles that pool money from multiple investors to purchase a diversified portfolio of securities. However, there are several key differences between the two:

Investment strategy: Index funds are designed to track a specific market index, such as the S&P 500, while mutual funds may follow a variety of investment strategies.

Management: Index funds are passively managed, meaning they simply track the performance of a specific index and do not require a fund manager to make investment decisions. Mutual funds, on the other hand, are actively managed by a fund manager who makes investment decisions on behalf of the fund.

Risk: Index funds are considered lower risk than actively managed mutual funds because they rely on a market index rather than the decisions of a fund manager.

List of References

- Source: investor.vanguard.com

- Source: morningstar.com

- Source: blackrock.com